About That Tone Knob (or knobs)

A 250K Short Shaft Potentiometer

Funny story. I talk to lots of players and because I am curious I ask often about the use of control knobs on guitars and basses. Some players use the volume knob a lot, some very little and some say it’s wide open all the time. Tone controls however, appear to be the unloved hanger on, and while some players get a lot of use from them, the overall average skews heavily to “leave it at ten and forget about it”.

Which begs the question”why” question, and the most common answer is that the player doesn’t like what happens to their tone. Words, like muddy, crushed, no highs and dead are often used.

I do use tone controls on instruments, but like many, I don’t get a lot of joy from them, so let’s take some time to explore the design and delivery of the tone potentiometer and then consider how to make it more useful, or if it can be more useful, or if we should all follow Edward Van Halen and remove it completely and deal with tone shaping elsewhere.

The Tone Potentiometer

We will start with the design behind what we know most often, the passive tone circuit. A potentiometer is a variable resistor. When turned all the way up (let’s call that at 10), in theory it has no effect at all on the signal moving through it. This is not always true, it really depends on the design and build quality of the potentiometer itself. A Tone pot has a capacitor soldered into the circuit. As the tone pot is turned down, high frequencies are reduced.

The micro farad rating of the capacitor has impact on how much the highs get rolled off and the capacitor is also working in conjunction with the resistance value of the pot itself.

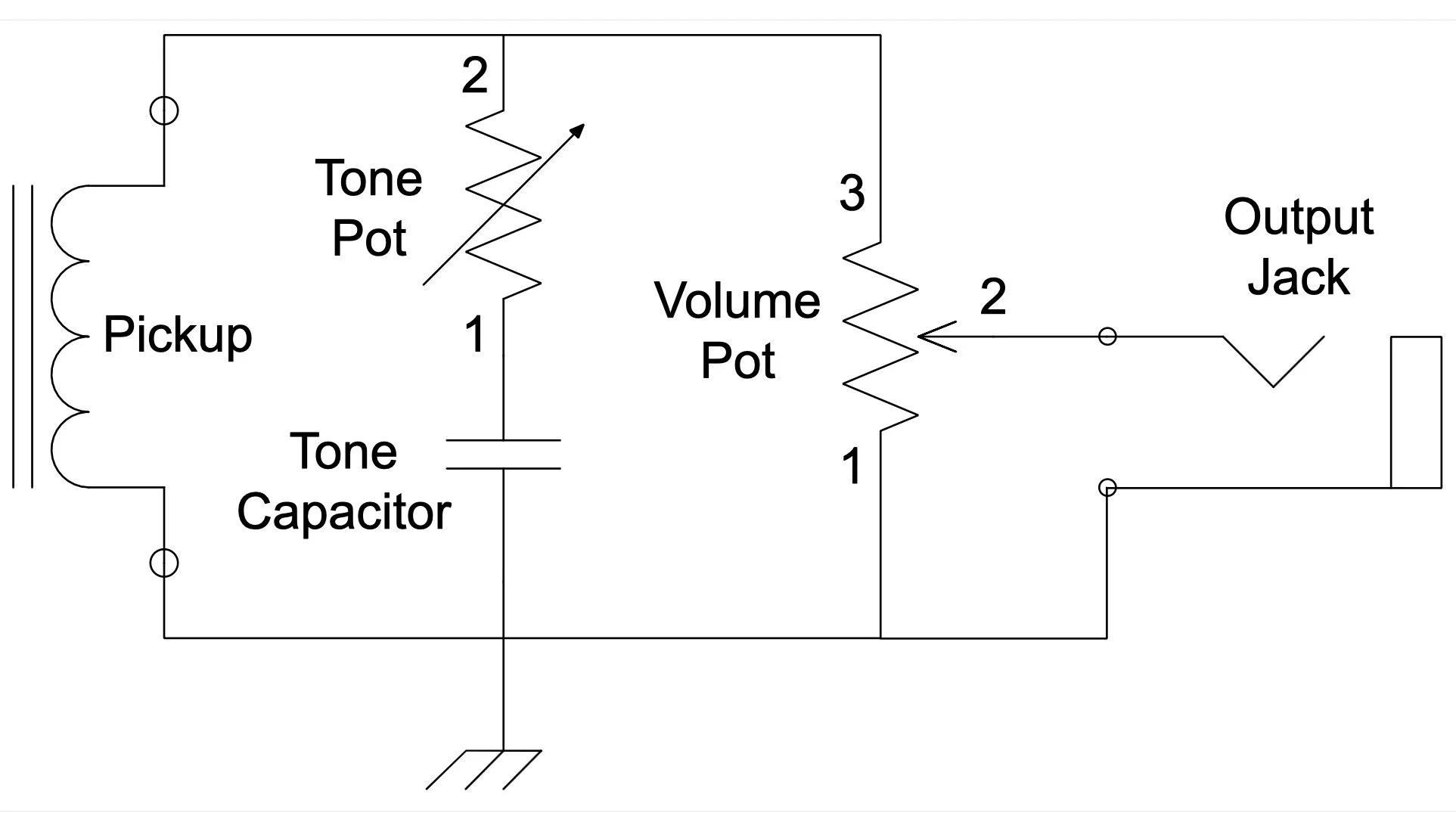

In reality, the signal from the pickup goes to the volume potentiometer which in the simplest world then sends the output to the output jack, ie no tone pot. However the general design is that the signal goes from the pickup to the volume pot and then to the tone pot where the capacitor is wired on one side to the wiper (the part that varies the resistance in the tone pot) and the other side to ground.

When the tone pot is rolled off, more of the higher frequencies get dumped to ground and we hear a bassier, and warmer tone. A more accurate name for the instrument tone pot is a low pass filter, meaning it passes low frequencies and filters out higher frequencies. So far so good.

Simple circuit diagram. Copyright Amplified Parts, All Rights Reserved

One other consideration can come into play and that relates to the taper type of the potentiometer. Most quality instruments use audio taper potentiometers where the pot changes on a logarithmic curve, but some makers use the less expensive and less useful linear taper potentiometers. I do not find that instrument makers describe what kind of taper that they use and in the overall context of signal path, particularly if you avoid the tone pot, it won’t matter. But for those who want to go deep, here’s a chart to show the difference.

Copyright Amplified Parts - All Rights Reserved

What Frequencies Get Dumped?

Now that is the right question. The tone circuit is incredibly simple. In fact, determining exactly which frequencies are getting dumped and by how much is not well documented at all. A tone pot, being a simple design, is basically a sledgehammer. The more you turn it down, the more highs get dumped, but unlike in a stereo loudspeaker crossover circuit, the cutoff and rolloff rates are neither published nor clear.

This rather hippo in a fishbowl approach is why many players hate the effect of tone pots. Sure there is endless Internet chatter about which resistance in the pot is best and what capacitor is best and everyone can have their own opinion, but it’s still very much using a shotgun to kill an ant. A more precise model would be the notch filters on some acoustic instrument amplifiers that use the wiper to knock out a specific narrow frequency range to help deal with feedback. Yes that is oversimplified but it paints an understandable picture.

The following table, courtesy of the fine people at Amplified Parts shows the impedance of a common capacitor in use on a tone control at different frequences. The impedance references how the capacitor passes low end while cutting high end. Typical the higher the capacitor micro farad rating, the more aggressive the high cut is. The 0.022 capacitors are commonly used with single coil pickups and the 0.047 capacitors are commonly used with humbucking pickups. The 0.10 capacitors are most often found on old electric basses.

Image copyright Amplified Parts - All Rights Reserved

How Do I Know if my Tone Pot is Actually Cutting Nothing at 10?

In a well designed pot, when the pot is up to full, or 10 in our example, the wiper is effectively disengaged and none of the signal goes to the capacitor at all. Some vendors offer what they call No Load Tone Pots, which have a detectable notch that you can feel when the wiper is fully disengaged. Whether there is an audible difference, and having instruments with both, I cannot tell and cannot find any credible scientific documentation either way. If you are really worried, you could install No Load pots, but there are a ton of other places in the overall signal chain that can be eating higher frequencies, the most obvious being the native capacitance in instrument cables.

The EVH Model

Mr. Van Halen was certainly not the first player to remove the tone circuits from his instruments but is possibly the best known of those who did. The only impact on the signal level in this case is the volume potentiometer. However, if you want some control over the overall tone, it has to be done somewhere.

The Amplifier Tone Stack

With most amplifiers there is at least a two stage tone stack, one control each for treble and for bass. Each is still just a potentiometer so any setting other than wide open is sending some element of the signal to ground. It’s funny that many players will leave the tone pot on the instrument wide open, but set the amp tone controls to a mid-level by default. Some amplifiers will add a midrange pot, and some will even break those into high mid and low mid pots. The more tone controls, in theory, the more finite control you have over your tone. However at a fundamental level, amplifier tone stacks are also passive and only cut, they do not boost so the potential issue has just been moved to a different place.

Getting More Control - The Equalizer

Before we get into this, a couple of thoughts. While an equalizer can be used to deal with different volume levels for different frequencies, if that’s all you use it for, you are definitely leaving money on the table. The second and to my mind more important thought is that when looking at a graphic equalizer, your goal is not accomplished necessarily by a smooth and pretty curve. It’s an audio tool, not a visual thing.

Pedal style equalizers have been around for a long time, typically in the form of what we call the graphic equalizer. Each slider (just a different design in a variable resistor) works in a specific frequency band and in theory has no impact on other frequency bands. So one has much more control to tailor the sound of the instrument. The challenge is that as players use different instruments, or play different tunes, the EQ may need to be changed and that may work easily in the studio, it may be less easy playing on stage. There are now digital EQ pedals that can store multiple EQ presets to make life easier for the musicians who need different EQ settings for different songs or stage scenes. Is this better than amplifier or instrument controls? Certainly, but one must then also do the work to negate the impact of other tone controls elsewhere in the chain unless one likes their tonal soup to be incredibly complicated. Most pedal equalizers are active, meaning that they boost or cut and often have a master level control as well.

I have bought, used and sold a number of what I call these live EQ pedals. A pedal that only gives me one EQ simply is worth little to me, so I prefer the digital ones. But you also want the capability for live tweaking without needing ten inch long spider fingers and octopus arms.

A very sucessful pedal has been the Boss EQ-200. It has a large, easy to read display and four presets plus a fully manual setting. It’s a well built pedal and does a solid job without getting all foo foo.

A bit smaller on the board but with more flexibility if you use their control software to program it is the Source Audio EQ2. Like the Boss it does graphic equalization but adds the ability to set the Q for each range, effectively giving you a parametric capable EQ on your board. I like it very much, and use one consistently with amplified acoustic guitars, especially if there are Piezo pickups involved. I also use this when a guitar has both traditional pickups AND a piezo for “acoustic” tones. It takes a bit more work to learn, but in my opinion, the Source Audio EQ2 is my general go to.

Another potential pedal for consideration comes from Ibanez and is called the Pentatone EQ or PTEQ. While it looks like a graphic equalizer, it is in fact a true parametric equalizer only. Where the Boss is a great graphic EQ and the Source Audio is both a graphical and parametric equalizer, both with presets, the PTEQ is a parametric equalizer that has a simple to learn and use interface that reminds me of the superb SAE Parametric EQ rack unit, I lusted after in the late 1970s. The PTEQ is also included in the PTPRE which combines a preamp system and the EQ together and also adds a simple noise gate. The only downside from my perspective is the lack of preset options, so if you need different tonal landscapes, you either have more than one, or you tweak between songs when playing live.

So if you want an EQ pedal with presets, consider one of the two options I refer to. If presets are not needed, the Pentatone has a short learning curve and is really good sounding. They are all easy to use, have presets and are large enough that you can tweak the unit live if you need to.

In The Studio

When you are recording, you may not be using your pedals very much or at all. When I was apprenticing in the studio, I expected to see all these multiband graphic equalizers. I was wrong. What I found instead were multiband parametric equalizers. These devices would be set by the engineer and / or the producer to manage very specific frequencies, the width or Q of the frequency band and either the boost or the cut. Not passive devices, and requiring more skill to use well. Today as a recordist, I only use parametric equalizers in my DAWs, and I have a number of different ones, because they do actually impart different sound feelings from model to model. I find myself using Pultec equalizers most often, but it really depends on the sound outcome desired. Each track can have its own unique EQ setting, and then there may be (likely will) be final equalization and compression done in the mixdown and mastering phases. If you are not doing your own engineering and production, this may be a path you don’t worry about and choose to stick to instrument or amp or pedal eq work. However if you will be acting as a recordist, invest the time to learn how to use parametric eqs and take the rest out of the signal chain.

Wrapping Up

The Tone Pot does exactly what it was designed to do. Provide a simple, single knob that offered a quick way to cut treble, increase warmth, diminish the sound of pick attack, or fake out a deeper bodied more acoustic instrument. Yes it is a hammer, but if that’s the right tool, go forward. However if you are not thrilled with your tone, my advice is to turn all the tone controls on instruments and amps all the way up and use a digital EQ pedal with preset capability to get you the sounds that you actually want to hear.

If you like what I do here for you, please become a supporter on Patreon. Your monthly contribution makes an enormous difference and helps me keep things going. To become a Patreon Patron, just click the link or the button below. Always feel comfortable to send in a question or to post a comment. I read them all and respond as appropriate. Thanks for your support of my work. I’m Ross Chevalier and I look forward to sharing with you again soon.